This authority on T cells pivots to lend his expertise to tackle the new threat.

This authority on T cells pivots to lend his expertise to tackle the new threat.

“I’m amazed that initially — the first two, three months — everybody is only speaking about antibodies,” says immunologist Professor Antonio Bertoletti from the Emerging Infectious Diseases Programme at Duke-NUS.

As the pandemic unfolded, Bertoletti noticed public interest in antiviral immunity, his field of expertise, rising rapidly. Friends started asking him about his research.

Yet, the immediate focus on antibodies as the single most important measure of immunity failed to capture the whole story. To fully understand the body’s response to viruses like SARS-CoV-2, Bertoletti points to an overlooked group of immune cells

— T cells.

“In any viral infection, there are antibodies and T cells,” he shares. “Antibodies are easy to test, T cells are a little more complicated to test. But that doesn’t mean they don’t exist.”

T cells, the white blood cells that respond to viral infections, have two roles. Helper T cells, or CD4 T cells, survey the body for foreign invaders or pathogens and stimulate the production of antibodies. Killer T cells, or CD8 T cells, destroy cells

that have been infiltrated by viruses before they can replicate, alerted to the cells’ distress by the viral antigens hoisted like flags on the surface of the cells. These cells can eventually turn into memory CD8 T cells, ready to strike if

the same pathogen appears again.

Compared with antibodies, which prevent infection, T cells target and clear an infection after it has occurred. A robust T cell response can mean the difference between mild or severe illness.

Yet, while T cells are a critical pillar of immunity, they are difficult to measure, which means they are often overlooked by scientists, vaccine manufacturers and the media.

“Nobody believes in T cells,” Bertoletti says, with a wry chuckle.

Immunity from SARS-CoV-2

It is precisely these underdogs in which Bertoletti is interested. His laboratory researches the immunological control of persistent viral infections, those caused by particularly hepatitis B virus, and develops therapies that harness T cells to fight

recurring liver cancer caused by the virus.

In early 2020, as SARS-CoV-2 swept across the world, Bertoletti’s focus was quickly drawn to the new and deadly coronavirus.

“I did not think it could spread so fast, in such a short time,” he reflects. “Then everything exploded.”

Cases in Singapore rose steeply. Around the same time, Bertoletti’s hometown in Italy became one of the worst-hit areas. It was no longer a theoretical threat. But it had stopped being that even before then.

In March, Associate Professor Tan Yee-Joo from the National University of Singapore, a long-time collaborator of the Bertoletti lab, had reached out. She and Bertoletti had previously collaborated to understand the T-cell response to SARS-CoV-1, the virus

behind the 2003 SARS outbreak. Could Bertoletti now help test COVID-19 patient samples?

The answer was a resounding “yes”. And Bertoletti’s team was well-positioned to start testing immediately. They had on hand the necessary reagents from their earlier work on SARS-CoV-1.

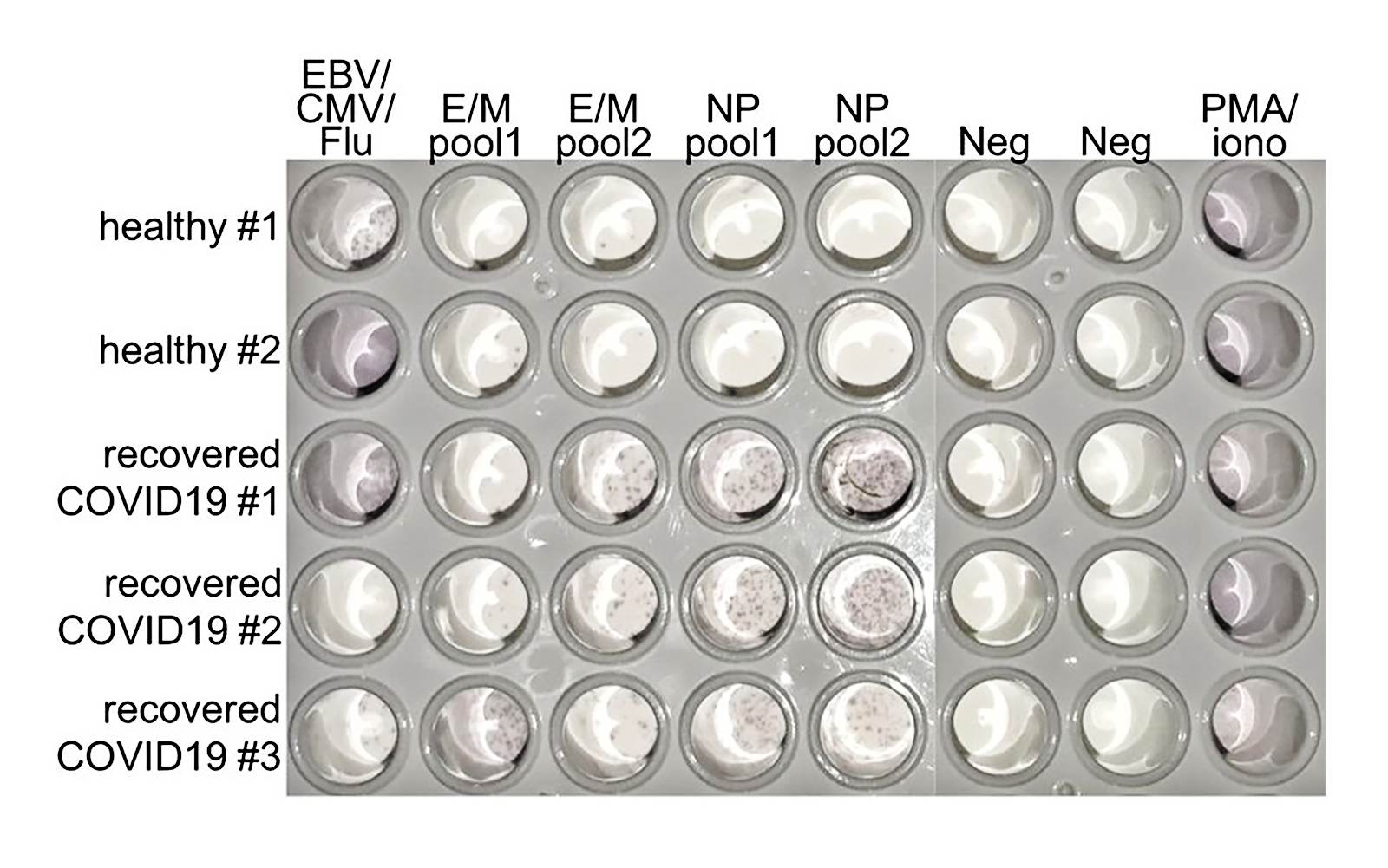

To understand how the body defends itself against SARS-CoV-2, the pathogen behind COVID-19, they used an enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISpot) assay, a method for monitoring T cells that actively secrete specific signalling proteins or antibodies.

On 6 April 2020, the lab tweeted a picture of their ELISpot results, with the question, “An alternative to the antibody tests?”. The post attracted hundreds of comments and more than 150 retweets.

“We ran the first ten samples and the response was fantastic,” Bertoletti enthuses.

THIS PICTURE OF AN ELISPOT RESULT SHOWED THE PRESENCE OF LARGE NUMBERS OF T CELLS IN COVID-19-RECOVERED PATIENT SAMPLES // CREDIT: BERTOLETTI LAB (TWITTER)

“It was one beautiful ELISpot,” stresses Bertoletti. “And it was the first one in all the world, basically.”

The interest of other researchers and clinicians was piqued.

That ELISpot marked the start of a frantic three-month-long sprint by the team to investigate the T-cell response of three groups of people: those who had recovered from SARS some 17 years previously, those who had been infected with SARS-CoV-2, and a third group of healthy volunteers who

had had neither SARS nor COVID-19.

The race ended today, with Nature publishing their findings. Like the tweet in April, the paper, titled “SARS-CoV-2-specific T-cell immunity in cases of COVID-19 and SARS, and uninfected controls”,

attracted immediate attention from around the world.

National Institutes of Health then-Director Francis Collins would go on to cite it in his blog on 28 July

2020.

Over the weeks and months that followed, the paper quickly became one of the most popular articles, cementing its place in the top one per cent of

tracked articles of a similar age well into the months and years to come.

Ever on the cutting edge

With the pandemic far from addressed, Bertoletti’s work on T cells would keep apace. Questions on the relationship between the severity of disease and T-cell response would require addressing. And with novel vaccines on the horizon, how

these stimulate T cells would be another piece of the puzzle that could help the world chart a path to living with the virus.

While these questions would need addressing, finding a way to measure T cells easily in a healthcare setting without specially trained staff would become another project of Bertoletti’s.

Through all this work, Bertoletti would become also an important member of a collaborative global effort to understand the contours of the pandemic.

“Before, we were much more niche, more isolated,” he observes, noting that much of the recognition for his previous work on Hepatitis B had come from Asia, where the virus is more prevalent.

His pandemic projects would put him in contact with SARS researchers in Europe, and foster new collaborations with other researchers in South Africa, Spain and the United Kingdom. “The community of immunologists working on SARS-CoV-2 is

now very active. We have nice discussions,” he shares.

That thriving sense fo community was evident in his own team, and had enabled them to press ahead with their research even when restrictions in Singapore were at the highest level.

“We were very, very united. We still are,” Bertoletti says, while acknowledging the pressure they were under. “It’s a little bit stressful. The pace is so fast, and [if] you want to be on the cutting edge, it’s difficult.”

“But we were there, and are still there.”