A Duke-NUS research team chats candidly about their mission to develop a dream vaccine.

A Duke-NUS research team chats candidly about their mission to develop a dream vaccine.

“Once we publish this New England paper, all the people who have access to it will immediately start their experiments to prove us right. Or prove us wrong,” says Dr Chia Wan Ni, a then-research fellow with Professor Wang Linfa’s lab at Duke-NUS. “So, we’ll be competing

with the whole world.”

“That’s science, right? You must muster a bit of competition. Then you become better,” adds her co-author and lab mate Dr Tan Chee Wah, a senior research fellow.

The paper that had both of them so excited appeared in the discipline-defining The New England Journal of Medicine, and provided the first glimpse of broadly

neutralising antibodies produced by SARS-CoV-1 survivors who had received the Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccine.

Neutralising antibodies that were powerful enough to fight not just SARS-CoV-2 and its variants of concern (VOC) but also other animal-borne coronaviruses that could trigger SARS-3 or SARS-4 — never mind that the SARS-CoV-1 infections took place

almost two decades ago in 2003.

“And if our science leads to a real product — like a real vaccine that actually can be used for boosters — then…,” Tan trails off, leaving the enormity of the thought unspoken.

“If it works, that means our science is true. And correct,” Chia chimes in. “It’s a good feeling to be validated by others.”

They laugh, in mixed satisfaction and disbelief, at how their work had escalated since the start of the pandemic.

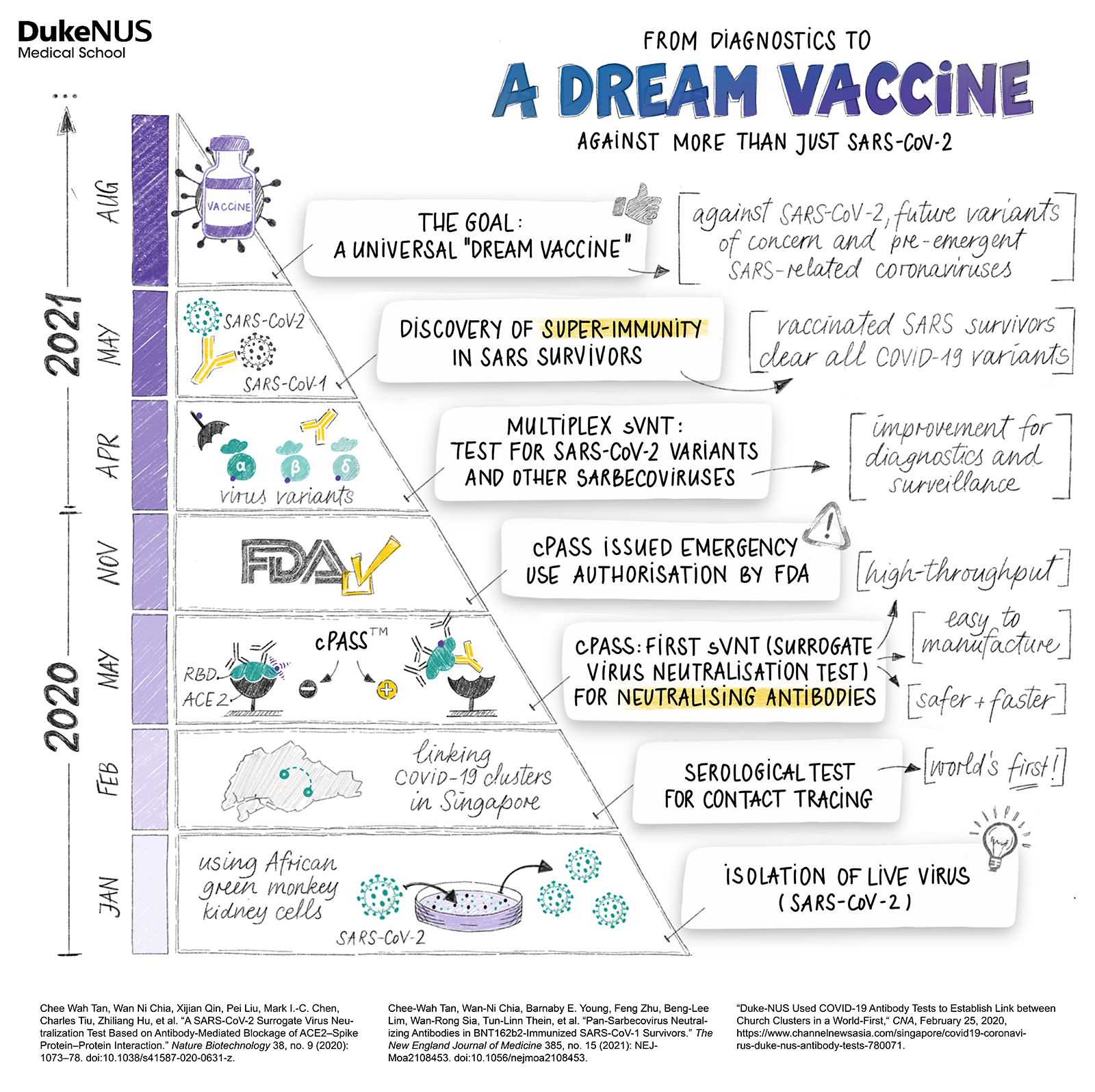

FROM DIAGNOSTICS TO A DREAM VACCINE, WANG LINFA'S TEAM USED THEIR NOVEL SURROGATE VIRUS NEUTRALISATION TEST TO IDENTIFY ANTIBODIES THAT FIGHT MORE THAN JUST SARS-COV-2

First, they were just doing their own research. Then their serological testing methods helped Singapore’s health authorities link two of the largest SARS-CoV-2 clusters; the cPass™ serological test kit for the rapid detection of SARS-CoV-2 neutralising antibodies followed.

Now, this New England paper; their laugh simply means Is this big breakthrough really happening? To us?

Expanding upon their breakthrough

They had possibly just hit the science jackpot. But after the long hours in the lab and at their desks as well as that frenzy of writing up the data and the month-long peer review fact-checking process, they felt like they were suddenly put on hold as

they impatiently waited for news from the journal.

Tan shakes his head. “When our paper was first accepted in principle, I kept asking Prof Wang, ‘When’re they officially accepting our paper? Are they going to reject us or what?’”

“Then after the official acceptance, I kept asking Prof Wang ‘When’re they publishing our paper?’” Tan continues, deadpanning. “It was a very long wait.”

Because until it was published, they could not share their excitement with the wider world nor receive the validation of other labs corroborating their findings.

“I think everyone of us has our secret tree hole to tell all these things to,” adds Chia.

Secret tree holes aside, the team relied on each other during these moments.

“It’s good to have someone to talk to, and just hash things out, and just feel amazed at the whole situation,” she concludes.

Also, the New England paper didn’t, Chia points out, mean the end of that particular research avenue for them.

“Now the question is whether people who’ve already been given the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, if they’re given a SARS-CoV-1 spike protein, will that have the same effect? That is what we’re testing,” she says.

And how do they feel about their increased prominence overall?

They are, after all, no longer just a lab working on their research. No. They are part of the larger, nationwide, even global, research work network intervening against the pandemic.

“Now we get to work with multiple parties and we get to see interpersonal relationships,” says Chia. “We get to know more about how things work in Singapore.”

“We can contribute to the country,” answers a quietly satisfied Tan. “So it’s good.”