Duke-NUS’s education team rallies for a second time to deliver clinical exams at the height of the Circuit Breaker.

Duke-NUS’s education team rallies for a second time to deliver clinical exams at the height of the Circuit Breaker.

Having delivered COVID-19-safe high-stakes clinical exams for the graduating cohort of medical students in March, the Duke-NUS education team could be forgiven for thinking that the worst was behind them.

When the Circuit Breaker was announced, the team knew they had to rethink their protocols again for the final round of clinical exams.

“I felt like MacGyver,” says Ms Kirsty Freeman, the then-lead for the Clinical Performance Centre at Duke-NUS, referencing the fictional

undercover agent with nifty invention and engineering skills. “We just had to use what was on hand.”

And the Circuit Breaker made necessity the mother of invention.

“We couldn’t go to shops and had no time to buy stuff online. We just had to use what we had and invent solutions through trial and error,” explains Freeman.

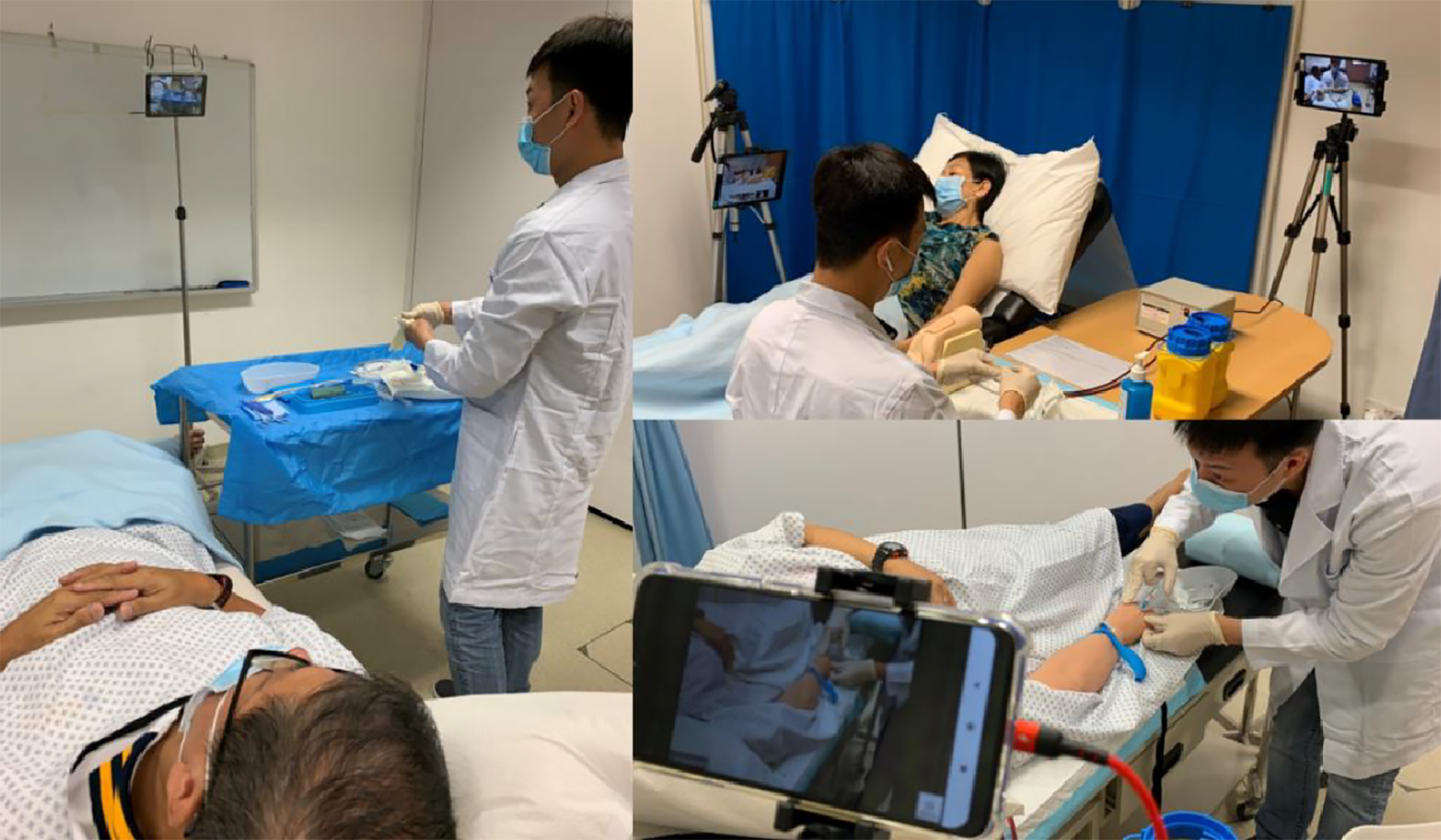

“Trial and error”, in this case, meant Freeman and her team repurposing duct tape to prop up mobiles and tablets, using plastic sleeves to hang cameras on walls and perching livestreaming cameras on intravenous poles.

“How could we position cameras to capture images? Who had duct tape and bits and pieces to bring in from home? Could we stick stuff on walls or lean tablets against equipment for a different angle? It was creative,” she laughs.

Going social for examination support

The Observed Structured Clinical Examinations or OSCEs, which officially concluded with their supplementary run in May, went smoothly. In addition to the MacGyver-style improvisations, Freeman and her team developed and executed a five-point operational

strategy. They minimised in-person interactions between students and examiners, limited the on-site number of simulated patients and faculty, robustly tested all their repurposed technological solutions, and familiarised every single OSCE participant

with the new arrangements.

A DUKE-NUS STUDENT COMPLETES HIS CLINICAL EXAMS, MODIFIED TO ADHERE TO THE TIGHTEST COVID-19 RESTRICTIONS IMPOSED BY THE SINGAPORE GOVERNMENT IN 202

Sixty-two medical students — who are part of the uniquely-trained Duke-NUS Class of 2020 — would graduate on 29 May.

The secret ingredient to this success, Freeman reveals, was going social. She credits informal sharing networks for bringing the medical simulation community together and preventing educator burnout. For instance, she actively crowdsourced best practices

and exchanged tips on topics such as manikin sanitation and hygiene protocols.

“Social media was such a great tool for everyone to share their stories. It’s the little things like what is it that we must do and how do we do it. The simulation community was coming up with processes and policies and guidelines to keep

everyone safe.”

And this sharing enabled Freeman and the Duke-NUS team to adapt quickly. “We could learn how someone tried something, and we could build on their successes and failures. That’s how we have been able to respond so quickly and implement

things effectively,” says Freeman. “It’s energising to know that we can provide solutions to challenges that other people, too, might be facing. None of us are alone in this.”

She thinks again, with a proprietary pride, about the graduating students.

“We delivered incredibly robust education while adhering to safety restrictions. We can say — with hand on heart — that our students are ready for the workforce. I think that’s spectacular.”

Freeman, along with their colleagues, would go on to publish their approach in MedEd Publish, which would be downloaded thousands of times as educators looked for

ways in which to pandemic-proof exams around the world.