The need for a self-sufficient Singapore motivates one researcher’s quest for a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine.

The need for a self-sufficient Singapore motivates one researcher’s quest for a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine.

“It is not unreasonable for countries to buy insurance in the form of vaccines to protect lives and livelihoods,” muses infectious disease expert Professor Ooi Eng Eong. “But better still would be for a country to be self-sufficient. We should be able to make our own vaccines.”

And he did more than just muse.

Putting his thoughts into action, Ooi leveraged his experience with dengue and SARS as well as his lab’s deep know-how about what makes an effective vaccine to embark on a quest to enhance Singapore’s vaccine expertise, test drive processes and protocols with the hopes of producing a new COVID-19 vaccine for the world.

That motivation — to contribute to a resilient and self-sufficient Singapore — made him and his long-time collaborator then-Associate Professor Jenny Low the perfect partners for biotechnology company Arcturus Therapeutics, which had a self-replicating mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccine concept and ready candidates that needed to be assessed, optimised and tested.

A known quality

The gravity of what was to come first hit Ooi in January 2020 when it was confirmed that a SARS-like virus was behind the outbreak.

Oh no, will this be a repeat of 2003? That was Ooi’s initial thought. The 2003 SARS outbreak had been testing for Ooi, standing out for its long days and short weekends. He’d unstintingly run experiments in one of Singapore’s two biosafety level 3 (BSL3) labs — the high-security facilities needed to study infectious airborne pathogens — for anyone who needed answers, and distributed inactivated viruses to colleagues for use as a control to ensure diagnostic equipment was returning accurate results.

And it was thanks to this experience that Ooi felt confident that Singapore was more prepared this time. SARS had been a watershed moment, highlighting the need for infection control infrastructure; an infrastructure that even had a dry-run in 2009.

He pauses briefly. “But the SARS label was also a bit of a red herring because we all thought that we should be able to control this outbreak as quickly as we had SARS,” he says. “That turned out to be wrong.”

Even as he authored one of the first close-ups of the inflammatory and immune response in patients infected with this novel SARS virus, he still thought — hoped — the outbreak could be contained.

“Those were the first three cases and I thought that would be it,” laughs Ooi, fully aware of how wishful that thinking turned out to be.

Embarking on a moon-shot collaboration

But as SARS-CoV-2 infections continued to spread in Singapore and around the world through undetected networks of pre-symptomatic and asymptomatic carriers, Ooi knew that as the co-director of the Viral Research and Experimental Medicine Centre at SingHealth Duke-NUS (ViREMiCS), he could — and should — intervene on a larger scale.

“It was mid-February when the EDB [Economic Development Board] asked if we would collaborate with a company they’d been talking to,” says Ooi.

Discussions between Duke-NUS and Arcturus started roughly a fortnight later. About a month later, with knowledge of how they could complement each other, both parties agreed to embark on this vaccine project together.

“After that, life became very busy,” deadpans Ooi.

Arcturus delivered their vaccine candidates to Ooi and his team for analysis. Unlike other mRNA vaccines, the self-replicating nature of this vaccine meant that the mRNA in the vaccine could be amplified in the body, making it possible to have an effective vaccine at a lower dose. The patient’s immune system responds by producing antibodies and other immune cells to fight off the spike protein’s simulated infection then and there while forming a lasting memory of the threat.

“We thought we could contribute because of what we’ve been doing with dengue and yellow fever. We understood what attributes to look for in a vaccine candidate,” explains Ooi.

After carefully and systematically studying the different candidates’ attributes, Ooi and his team identified ARCT-021 as the most promising. In their preclinical studies, the self-replication process boosted ARCT-021’s performance markedly when compared with other mRNA vaccines. But it was also the one part of the vaccine that had not been tested in humans yet.

“My worry was that no matter how well we looked at it during the preclinical stage, that there would still be a surprise when it goes into humans, resulting in unexpected side effects,” says Ooi.

After a stringent set of tests, the company and regulators greenlighted the first phase of human trials. Despite that, Ooi and his collaborator, Low, a senior consultant with the Department of Infectious Diseases at Singapore General Hospital (SGH), who led the clinical trials kept a careful watch for possible side effects in the volunteers.

“I was very nervous,” confesses Ooi. “I think I was nervous throughout the entire Phase I.”

During this phase, the clinical trial team administered increasingly higher doses of ARCT-021 to the volunteers. They stopped when those who received the highest dose showed the first side effects.

Then, it was over to Arcturus with the data and on to the next phase.

“The initial set of data was enough to support the start of Phase II trials,” says Ooi.

Indeed, today, the Health Sciences Authority gave the greenlight to proceed with the next phase.

Around the same time, Ooi and his team also began delving deeper into the data to decode the immune response, so they could be better prepared in the fight against the coronavirus, as variants of concern would clearly continue to emerge.

Reflecting on his involvement in the most hotly contested race in human history, Ooi admits that “it was a bit daunting” to be one of more than 100 vaccine candidates that had commenced development as early as April 2020.

With only a fraction of vaccine development projects progressing to Phase I trials eventually, he did not know what to expect.

“But we were able to take it through to the next stage of trials,” says Ooi with some relief.

“Each new phase of testing uncovered new lessons for us to learn and we’re now consolidating these lessons to explore ways in which to create other vaccines,” he adds.

With hindsight, would he have done anything differently?

“The one thing that I wish we could have done,” considers Ooi, “was to have the resources to do more than one vaccine. But other than that, I wouldn’t change anything. Because we were given an opportunity to use what we had learnt to benefit Singapore and the world.”

A stark inevitability

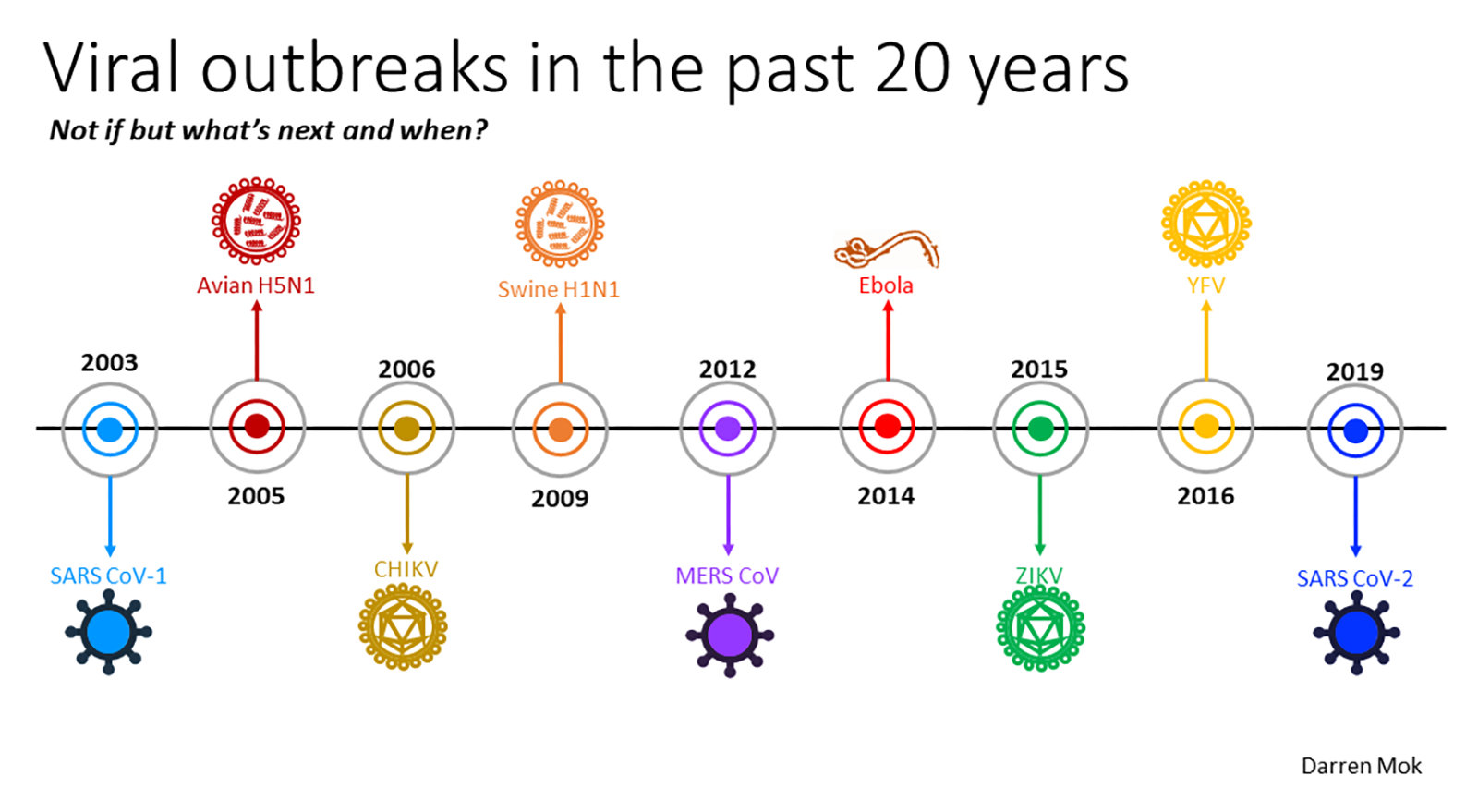

There is a slide Ooi is fond of showing during his talks. It charts a stark sense of the inevitable: the first twenty-one years of the 21st century alone have seen eight major disease outbreaks.

OOI'S SLIDE THAT DEMONSTRATES THE FREQUENCY OF OUTBREAKS // CREDIT: DARREN MOK / OOI ENG EONG

That means one outbreak every two-and-a-half years, which means the next one might be just around the corner.

“We need to invest in preparedness,” he says, noting that there is always talk about improvements and measures during outbreaks.

"We need to be self-sufficient,” he emphasises. “In Southeast Asia, we should not have to continually rely on shipping vaccines from Europe or North America,” he says. “To meet our needs, we should be able to make our own. And distribute it to our neighbours.”

Ooi also sees the experience gained from developing ARCT-021 as propelling future and further long-lasting healthcare solutions for the region.

He hopes that countries will invest in even more robust medical research ecosystems.

“Countries need to put aside a certain sum of money. Keep the infrastructure going,” he explains. “So that when you need, you can tap into that science.”