From Hendra to SARS-CoV-1, Wang Linfa brought all this experience to bear in the fight against COVID-19.

From Hendra to SARS-CoV-1, Wang Linfa brought all this experience to bear in the fight against COVID-19.

“It took me six months to convince the FDA,” says Professor Wang Linfa about the road to getting his invention — a simple yet impactful solution

to easily test for neutralising antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 — authorised for emergency use by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) today. “Many 3am meetings.”

The test, called cPass™ which he’d developed with his team at Duke-NUS, is one of Wang’s many contributions to help the world combat the pandemic. It detects whether a person — or animal — has been exposed to the SARS-CoV-2

virus or vaccinated against it. It does this by detecting, from a serological sample such as blood, if a person has the specific antibodies which neutralise the virus. It does this without the need for a live virus or cells and delivers results in

just an hour. cPass is, in sum, a world-first invention.

WANG LINFA AND HIS TEAM PROUDLY PRESENT THEIR INVENTION — cPASS™, A NOVEL WAY TO DETECT NEUTRALISING ANTIBODIES

“In the history of the FDA, they have never approved serology to measure neutralising antibodies,” notes Wang. “Not just for SARS-CoV-2 for any virus. The reason is that testing traditionally can only be done with live agents —

live viruses and live cells.”

“So how can you regulate it to make sure that that assay is performed identically in thousand different labs? There’s no way. Quality assurance is impossible when you have a live virus in a live cell. ‘Wow’, I thought, ‘that’s

a very high bar to cross.’”

But since cPass does away with this need, governments, as well as clinicians and researchers, can use cPass to measure immunity in the community, trace close contacts and evaluate vaccines and therapeutics.

“We still don’t really know how this pandemic started and we still didn’t know how we could get out. That was my focus,” says Wang. “Because if we don’t know how it started, we cannot prevent another pandemic.”

“And,” Wang pauses for emphasis here, “the old, powerful serology; it’s highly specific. The serological approach can play a key role in answering those problems.”

Lessons from horses to bats

Serology is the study of antibodies in blood and for Wang, a tried-and-tested strategy to get answers long after the virus has moved on. And Wang has 30 years of experience conducting such investigations — most notably during the 1994 Hendra

virus outbreak in Australia and the 2003 SARS outbreak in Singapore and Asia.

The Hendra outbreak, remembers Wang, was the moment when the full potential of serology became clear to him. In those days, he had worked at the Australian Animal Health Laboratory — now the Australian Centre for Disease Preparedness—under

the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO). And Hendra, named by Wang after the Brisbane suburb from which it originated, is a virus that can be fatal to horses and humans. It causes haemorrhages, meningitis and

respiratory dysfunction such as a build-up of fluid in the lungs.

Hendra’s transmissibility from its natural reservoir to humans, though, was not understood initially. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests of tissues taken from different animals, which the research team collected in order to study the

virus’ origin, all turned up negative.

“So, I said, ‘Serology’. Let’s go searching for Hendra virus antibodies and we’ll test as many different animals as possible,” Wang continues.

“We tested 42 different animals. Koalas, snakes, birds—everything. Eventually, we found an antibody in bats,” recalls Wang who found these antibodies in a particular type of bats called flying foxes, or bats of the genus pteropus.

With this knowledge, more precise laboratory research and public health measures were implemented against Hendra.

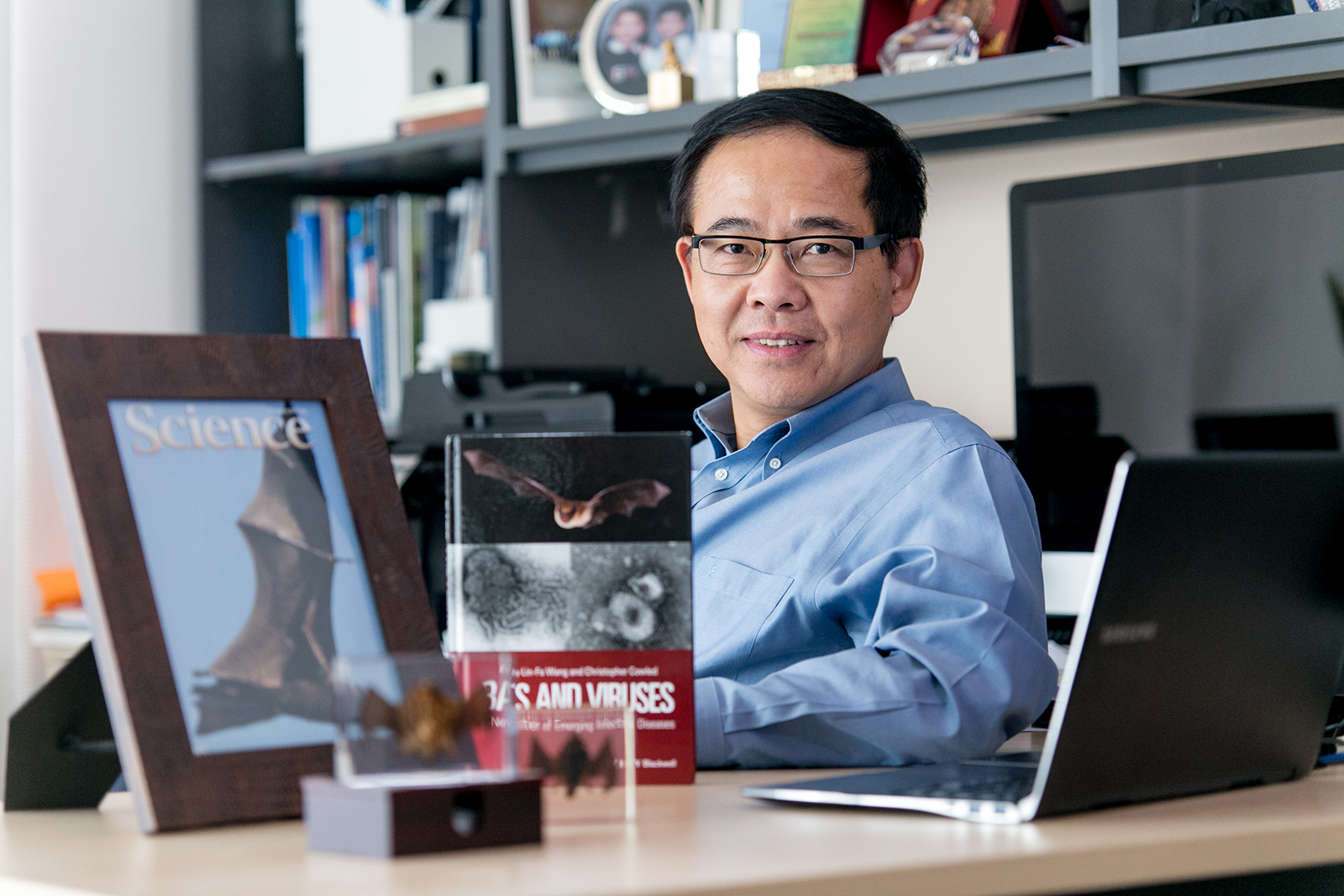

WANG LINFA IS ONE OF THE WORLD'S LEADING EXPERTS ON BAT-BORNE VIRUSES AND BAT BIOLOG

He brought the same expertise to curb the deadly Nipah virus outbreak which killed 109 out of 276 people infected in Singapore and Malaysia between 1998 and 1999.

As Wang pursued serological testing, though, he soon came up against its limits.

“In our field, we always say that the gold standard is the virus neutralisation test. But for virus neutralisation tests, you need a live virus for the base,” explains Wang. For diseases like Hendra and Nipah that meant Wang and

his team could only handle them in the most secure facilities, a biosafety level 4 lab. That made the job so much harder for them.

“I needed something that was a surrogate, so we could mimic this,” says Wang.

“So instead of using the whole virus, we just used a piece of protein,” Wang continues. That concept, developed using the Nipah virus, Wang published in 2007 to little fanfare.

Regardless, his surrogate method made testing for viruses easier, which, in turn, unlocked more data at a faster rate for policymakers, doctors and other researchers.

And cPass, the most current iteration of this concept, which Wang developed with his team at Duke-NUS, works exactly along the same principles of surrogacy and usability.

“We envisaged very early on that neutralising antibody testing would be important,” notes Wang about the anticipated bottleneck in testing. “[We] just wanted to do something that’d solve that issue.”

A proposal for the world

cPass may emerge as an internationally renowned intervention against the pandemic. And Wang’s own star rose to new heights; his network grown exponentially among fellow scientists and decision-makers. But Wang believes that he can play an

even bigger role.

“The dream for me is that one day — one day — people can treat viruses and pandemics totally apolitically. Treat them as a common enemy,” he says. “And then, in peacetime, build-up an intelligence, resource and knowledge-sharing

network.”

“That, to me, is the only way to prevent the next pandemic.”

Wang thinks for a moment about his contributions.

“I’m very proud that we have cPass. And we had something else very significant in the pipeline. But that’s less than 50 per cent,” he says. “The more than 50 per cent is the political will and the international system and mechanisms

to work together and achieve early warning, early prevention.”