To evaluate whether the Singapore model of ACP, based on Respecting Choices Model, enables patients to receive end-of-life care consistent with their preferences, we conducted a randomized controlled trial among patients with advanced heart failure. We randomized 282 patients to receive ACP or usual care. We analyzed data of 89 deceased patients from the trial. We found that deceased patients in the ACP arm were not statistically more likely than those in control arm to have their preferences followed for end of life care (ACP: 35%, Control: 44%), or place of death (ACP: 52%, Control: 51%). A higher proportion in the ACP arm had wishes followed for cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR; ACP: 83%, Control: 62%) but again the difference was not statistically significant. (2)

While there can be several reasons why our trial did not find that the ACP program to be effective in facilitating end-of-life care consistent with patient preferences, one possible reason is that patients’ preferences for end-of-life care change over time but ACP documentation is rarely updated over the course of patients’ illness.

To understand why patients’ preferences for end-of-life care change over time, think about the last time you have gone grocery shopping on an empty stomach and found yourself buying more food than what you will need for the coming week. In essence, our prediction for how much food we need for the coming week is being biased by our current state of hunger and we are making future decisions based on how we are feeling right now. This phenomenon is known as projection bias.

Projection bias is particularly problematic when there is a mismatch between what we are feeling at the moment and what we will feel in the future. It has important implications for ACP.

If during ACP discussions, patients make decisions for future end-of-life care based on what they are experiencing or feeling in that moment rather than what they are very likely to experience at their end of life, then the preference they record in their ACP may not reflect what they may eventually want at their end of life. Given that patient’s health status often fluctuates at the end of life, they are likely to change their preference for future end of life care frequently depending on what they are experiencing in the moment.

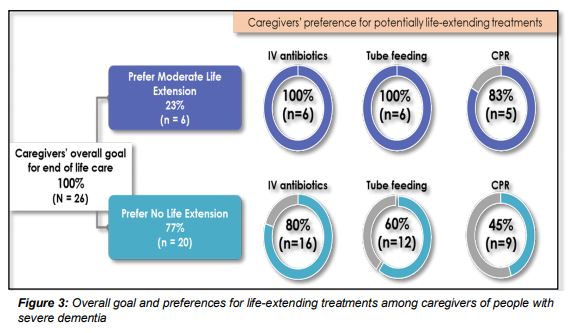

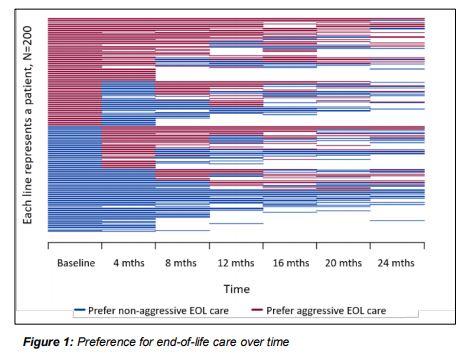

We used data from the above-mentioned randomized controlled trial to test the extent to which patients’ preferences for end of life care change over time. We found that out of the 200 patients with advanced heart failure interviewed every 4 months over the course of 2 years, 64% changed their preferred type of end of life care (aggressive versus non-aggressive) at least once (Figures 1, 2) and 66% changed their preferred place of death at least once. Notably, change was not consistent in one direction and was influenced by patients’ understanding of their prognosis (whether or not their illness can be cured) and their quality of life at the time of eliciting their preference. (3, 4)

We also assessed this phenomenon using data from a prospective cohort study of patients with an advanced (Stage IV) solid cancer (COMPASS: Cost of Medical Care of Patients with Advanced Serious Illness in Singapore). Among 466 patients with an advanced cancer followed-up for a period of 2 years, more than a quarter changed their preferred place of death every 6 months. Again, change in preferred place of death was not consistent in one direction. Patients hospitalized in the last 6 months were more likely to change their preferred place of death to home. (5)

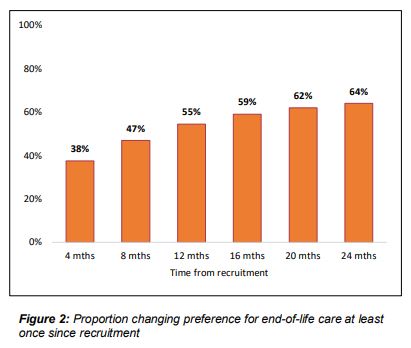

Lastly, we assessed whether preferences for life-extending treatments align with overall goals for care. We used data from a qualitative study with 26 caregivers of persons with severe dementia (part of the project PISCES: Prospective Longitudinal Study of Caregivers of Community Dwelling Persons with Severe Dementia). We asked caregivers about their overall goal of care for their care-recipient with severe dementia and their preference for intravenous (IV) antibiotics, tube feeding and CPR. Most caregivers’ (77%) overall end-of-life care goal was ‘no life extension’. However, of these, 80% still preferred IV antibiotics for a life-threatening infection, 60% preferred tube feeding and 45% preferred CPR (Figure 3). (6)

We also assessed this phenomenon using data from a prospective cohort study of patients with an advanced (Stage IV) solid cancer (COMPASS: Cost of Medical Care of Patients with Advanced Serious Illness in Singapore). Among 466 patients with an advanced cancer followed-up for a period of 2 years, more than a quarter changed their preferred place of death every 6 months. Again, change in preferred place of death was not consistent in one direction. Patients hospitalized in the last 6 months were more likely to change their preferred place of death to home. (5)

Lastly, we assessed whether preferences for life-extending treatments align with overall goals for care. We used data from a qualitative study with 26 caregivers of persons with severe dementia (part of the project PISCES: Prospective Longitudinal Study of Caregivers of Community Dwelling Persons with Severe Dementia). We asked caregivers about their overall goal of care for their care-recipient with severe dementia and their preference for intravenous (IV) antibiotics, tube feeding and CPR. Most caregivers’ (77%) overall end-of-life care goal was ‘no life extension’. However, of these, 80% still preferred IV antibiotics for a life-threatening infection, 60% preferred tube feeding and 45% preferred CPR (Figure 3). (6)

Given preferences change over time and may not necessarily align with patients’ values/goals, we argue that most patients/caregivers do not hold well-formulated and strongly held preferences regarding what forms of end of life care they want.