Dr Shravan Verma is full of ideas and has a knack for building things. And inspiration can strike him any time. Like late at night while plagued by pain.

In 2016, the Duke-NUS Class of 2014 alumnus suffered a sports injury. With his pain worsening late at night, he realised the only option for him to get strong enough painkillers at that hour was to head to an emergency room or a 24-hour clinic. But as a doctor himself, he balked at the idea, reluctant to put unnecessary strain on the medical system.

That’s when the idea came to create an app to allow users to seek medical care and services from home came.

“I felt like I couldn’t be the only one facing such an issue, so there was a gap in the system,” recalled Verma, who pursued his MD after earning an undergraduate degree in biomedical and electrical engineering from Duke University.

During his own rotation as a junior doctor in the emergency department, he saw patients coming in for minor things like constipation having to wait several hours. “There was nowhere else for them to access the care they needed,” Verma said.

Speedoc is the brainchild of Duke-NUS alumni Dr Shravan Verma who wanted supplement out-of-hospital care options // Credit: Speedoc

Three years after graduating, he started Speedoc to supplement the traditional centralised care model that hospitals provide. Speedoc provides people on-demand access to doctors and nurses from the comfort of their own homes. It also supplies the necessary remote monitoring equipment. As Speedoc, Verma saw his first patients on 1 January 2018.

“The first two years were super challenging. I felt like I was on call 24/7,” recalled Verma. “At that time, our reputation and credibility was on the line, so I wanted to make sure that they were managed safely.”

Inspired to transform care, improve lives

Verma is one of more than 550 doctors from 11 cohorts who have graduated from Duke-NUS over the last 16 years. These clinicians hail from all walks of life and all around the world. They brought with them a diverse range of educational and professional backgrounds that has given them unique perspectives on medicine.

Yet, the desire to improve the healthcare and make a positive impact on the community they serve has been central to the pursuits of Duke-NUS’ Clinicians Plus—all the way from the graduates from inaugural Class of 2011 like Dr Cecilia Kwok to members of the School’s pandemic cohort such as Dr Lim Gim Hui from the Class of 2020.

In addition to the research-intensive medical training, Duke-NUS fosters compassion and collaboration as well as analytical thinking through its flipped-classroom team-based TeamLEAD teaching pedagogy as well as initiatives such Project DOVE.

Through Project DOVE, which is short for Duke-NUS Overseas Volunteering Expedition—established in 2010—students have been reaching out to neighbouring countries since 2010. In 2019, the Project DOVE team was recognised with a Student Life Award by the National University of Singapore for its significant contribution to the university outside of academia.

Then a medical student at Duke-NUS, Dr Lim Gim Hui, pictured here with villagers from Khe Sanh, drew on his experiences from humanitarian missions to contribute to the success of Project DOVE // Credit: Lim Gim Hui

That year, 18 Duke-NUS students, accompanied by six faculty members and 18 volunteers from Project Vietnam foundation, their in-country partner organisation, served more than 1,000 patients in the rural community of Khe Sanh in Vietnam. They also raised the most money for the project since its inception which they used to improve sanitation at a local preschool.

One of the three project leads that year was Dr Lim Gim Hui, who drew on his experience from his years of serving with the Singapore Armed Forces to help the team achieve these milestones. Lim had taken part in numerous humanitarian missions while serving with the Singapore Armed Forces, performing roles such as transporting medical personnel and equipment to communities in Indonesia and the Philippines.

Having discharged his duty to deliver supplies and personnel, Lim would tag along with the medics to the field hospitals and observe their craft.

Those experiences changed the direction of his dreams. With a degree in biological science, he wanted to find a way to put this knowledge to good use to better serve the community.

“I saw how impactful healthcare was, especially to communities that were extremely remote and lacked their own healthcare infrastructure,” said Lim.

Growing into Clinicians Plus

Since graduating in the middle of the pandemic, Lim has completed his first year as a house officer training and started on his residency in preventive medicine at the National University Health System.

“Through my residency training, I hope to gain perspectives on problems within our healthcare systems. I also wish to learn to create and implement effective healthcare policies to better the lives of people around me,” he added.

He has also returned to the armed forces as a fully registered Medical Officer serving as Section Head for the Medical Plans and Doctrines Branch in the country’s Navy Medical Services.

Dr Lim Gim Hui is now back with the Navy where he cares for fellow servicemen and women // Credit: Lim Gim Hui

While returning to the Navy may be a home coming of sorts, Lim brings with him new experiences gained through Duke-NUS’ flipped-classroom pedagogy and research-intensive third year in particular.

“Medical school provided me with an understanding of how our healthcare system works. More importantly, Duke-NUS taught me relevant skillsets to think critically and work with teams to design innovative solutions within resource limitations,” he said, crediting the research year in readying him to plan and execute many of the clinical trials he is running now.

Similarly, in creating Speedoc, Verma not only wanted to improve access to care but also change the lives of people across the region.

“Across Southeast Asia, there are about nine to ten hospital beds per 10,000 people, when the global average is about thirty beds,” he explained. “Governments could build more hospitals, which have large fixed infrastructural costs, or with a model like ours, we could turn any bed into a hospital bed as and when needed.”

While the pandemic may have slowed those plans, the core team has, nonetheless, grown to 150 full-time employees across three countries in response to an explosion in demand for telehealth.

And from partnering with just one tertiary healthcare institution before the pandemic, Speedoc now collaborates with five hospitals and a major insurance partner that refer their patients to receive treatment via its hospital home-ward services.

“The whole pandemic situation has made us realise that the model of people going to hospitals is probably not sustainable,” Verma said. “The pandemic really helped accelerate the behavioural change and adoption of services like ours, both from the consumer side as well as the partners.”

Improving lives during the pandemic

It is not only in the realm of creating new technologies that our alumni are helping the community. To Dr Maverick Uy (Class of 2013), lending a helping hand came in the form of mobilising his fellow residents and colleagues to donate their $600 COVID-19 Solidarity Payment to the needy. Together with his COVID-19 Junior Welfare Committee members from the Singapore General Hospital (SGH) Division of Medicine. Drs May Anne Cheong and Trina Arifin (Class of 2014), he started the SGH Solidarity Pledge.

“I think as doctors, we were quite fortunate, despite being frontliners. We were financially stable and didn’t lose our jobs,” said Uy, who is in his last year of training in his cardiology residency. “We were all given the same support from the government when some people needed it more.”

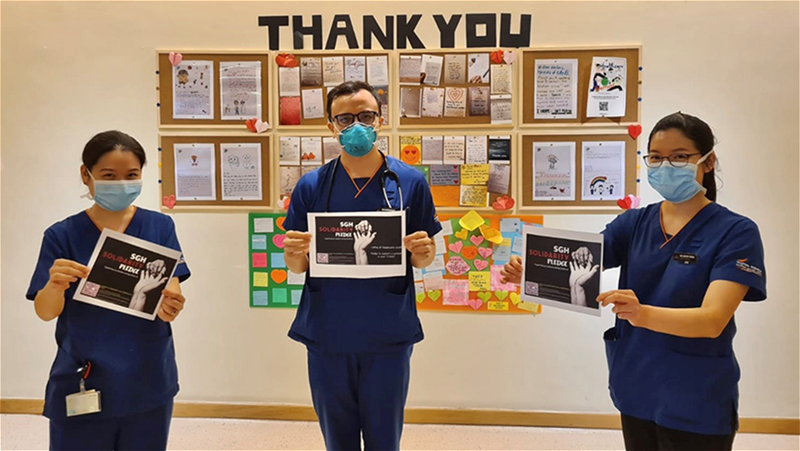

Drs Cheong May Anne, Maverick Uy and Trina Arifin celebrate the success of their project which started with an WhatsApp message // Credit: Than Zaw Oo

Thinking they could not be the only ones who thought that way, the trio sent out a message on their COVID-19 Welfare WhatsApp group. Over time, and help from the SingHealth leadership, they raised close to $60,000, which went to the SGH Needy Patients Fund and Healthy Communities Fund.

Elsewhere at SGH, clinician-researcher Dr Karrie Ko, who works in the division of pathology, had just started on her PhD in microbial genomics and metagenomics when the pandemic struck.

“It was an unforgettable Chinese New Year,” said the Class of 2011 alumnus and former Shaw Foundation Scholarship holder who graduated top of her class.

Over the holiday weekend as the first cases trickled in, diagnostic capabilities had to be ramped up so that the department could deliver the best testing service to patients and service partners.

With her speciality being in clinical microbiology and sub-speciality in molecular pathology, Ko’s niche skills came in handy when her team had the job of sequencing the genome of every COVID case at SGH to monitor and prevent inpatient clusters.

Dr Karrie Ko at work during the height of the pandemic in 2020 // Credit: Koh Tse Hsien

“We sequenced all the COVID-19 samples to analyse all the genomes so we could better understand how the virus spread and how cases were connected,” said Ko.

Later on, she also took part in research projects to ensure that the right infection control measures were in place to contain the virus within the hospital environment and community care facilities.

“It was extremely rewarding—although tiring at the same time—to directly apply the new knowledge and skills from my PhD to make a positive impact on real-world hospital care. It made me grateful for the Shaw Foundation Scholarship all over again because without it, I wouldn’t be doing any of this,” said Ko.

Driving change for a better tomorrow

However, the mental toll that physicians face, especially during a prolonged pandemic like this one, can be extremely challenging. Duke-NUS Clinical Assistant Professor Cecilia Kwok, Ko’s former classmate and now a consultant with SGH’s psychiatry department, is familiar with the stresses of working in the medical field.

Drawing inspiration from her own time as a psychiatry resident, she conducted a study on the high risk of depression and burnout among psychiatry residents, and is interested in extending it to medical students as well.

Now a clinical assistant professor, Dr Cecilia Kwok hopes to improve mental wellbeing among medical students as well as junior doctors // Credit: Singapore General Hospital

“It’s a perennial problem. But before we can even begin to solve it, we need to know beyond just anecdotes of ‘this student is stressed,’ or ‘that student is feeling overwhelmed’,” Kwok said Kwok. “After the COVID situation calms down, it’s something I’m interested in working on, and maybe collaborating with Student Affairs to look at the mental wellbeing of students as well.”

Beyond just conducting research, Kwok, whose first degree is in Biomedical Science from the University of Central Queensland, was also inspired to take on a role as a clinician-educator to improve the education of students in her alma mater.

“I both teach and plan the curriculum for the psychiatry component of Year One and Two,” she said. “On top of coordinating, I get to mentor the students and see everyone for feedback and to check on how they’re doing.”

A multitude of dreams

With all the different backgrounds Duke-NUS alumni come from, it is no surprise that their goals will be vastly different, yet equally interesting.

While Uy advocated for needy patients during the pandemic, he has also been a long-standing ambassador for Duke-NUS alumni. His term as president of the alumni association may be up, but he continues to champion an open-door policy for his fellow alumni.

“We always wanted to build this culture and community where Duke-NUS alumni are very open to each other,” said Uy. “For those just starting out, they may see me as so far down, but I do hope to break that barrier. In the ideal setting, they should feel to reach out any time.”

Uy is continuing to strengthen the Duke-NUS alumni network, Ko hopes to build a network of a different kind. Drawing on her experience from the pandemic, she hopes to deploy microbial genomics to the clinical forefront and build a sustainable surveillance programme for infectious disease detection and control. Her time at Duke-NUS, with fellow students and colleagues of different backgrounds has made her interested in interdisciplinary approaches to making that happen.

“I feel that I’m in a very strange and unique position to make that happen, because I am a clinical microbiologist with a molecular diagnostic interest and, at the same time I’m learning to speak the language of computational scientists,” she said.

For others, their plans are quite literally out of this world. Being a doctor in the armed forces will have Lim complete not just one but three specialisations. In addition to his residency in preventative medicine, he is pursuing specialist training in diving and hyperbaric medicine with the Navy Medical Service, and has plans to pursue aviation medicine to support his air force colleagues who are deployed at sea.

With land, sea and air medicine covered, space is the next frontier Lim.

“Being near the equator, our region provides valuable opportunities for space travel in the near future,” said Lim. “With training in both hyperbaric and aviation medicine will hopefully allow me to better serve my patients in future.”

Additional editing by Nicole Lim, Senior editor