Standing on the tarmac, Duane Gubler was arguing with the PanAm pilot. He had precious cargo, painstakingly collected over six weeks, and needed to get back to the lab in Hawaii. With flights few and far between, he simply had to be on that flight.

The specially insulated vacuum flask, containing mosquitoes and human blood samples, was rapidly running out of liquid nitrogen. And the airline’s agent at Samoa’s airport had refused to book him and his cryogenic storage dewar on the flight.

“Luckily, the pilot agreed to take the container on board,” Gubler writes in an upcoming memoir. “I had less than two inches on my measuring stick when I arrived at the laboratory in Hawaii.”

Gubler set off for this and similar field trips to the South Pacific to track the first dengue outbreaks in the South Pacific since World War II.

“I go where the action is,” said the dengue expert, earning himself the epithet “Indiana Jones in a lab coat”.

.png?sfvrsn=7d95b5f4_0&MaxWidth=800&MaxHeight=&ScaleUp=false&Quality=High&Method=ResizeFitToAreaArguments&Signature=3CA798E60D67ADFABEC40CF4FE078D68B04303D5)

Working “Indie”-style on these trips meant that any given day, he could be taking clinical histories, bleeding patients, performing lab tests or conducting entomological surveys and mosquito taxonomy.

This period spent chasing outbreaks set the tone for Gubler’s career, which he dedicated to advocating for and building sustainable programmes and networks to conduct active surveillance, convinced that the world had to monitor viruses in order to prevent or at least be prepared for an outbreak.

“His emphasis has always been on prevention,” said Annelies Wilder-Smith, a professor of emerging infectious diseases at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, who has known Gubler for more than 20 years. “The whole wait-and-see approach to outbreaks really upset him.”

Escaping the ranch

Gubler grew up in a ranch town in America’s Mountain West, shepherding cattle between Utah’s Pine Valley Mountains and the southern hills of St George. He supplemented his ranching salary with driving a produce truck.

“It wasn’t long before I realised that driving truck was not what I wanted to do for the rest of my life,” reflected Gubler. “But there wasn’t a lot of opportunities to do much of anything, except hard work.”

So, he took what he could—a good work ethic, belief in fairness and honesty and confidence in his decision-making—and headed to college, where he eventually majored in biosciences, encouraged by his zoology teacher, Wesley Larsen. Larsen also hired Gubler to work with him in the lab, studying the life cycle of cockroaches.

But it wasn’t this particular arthropod that captured Gubler’s imagination. While learning about the diseases that had caused the plagues of the past, he was enchanted by the villainous mosquitoes at the heart of many of these tragedies.

“It was a romantic thing, I think,” mused Gubler, “and somehow, as a young man, I had this romantic notion of working in the tropics, solving public health problems.”

That dream led him to earn a Doctor of Science in Pathobiology from Johns Hopkins University’s School of Public Health in 1969, graduating into what he calls a “scary time” in his life.

Following public declarations by prominent public health figures and institutions that the war on infectious diseases had been won, jobs studying these and their vectors had dwindled. The heyday of infectious diseases field work was over. Gubler, who, having married his high school sweetheart at the age of 18, also had a young family to think about, accepted a teaching post at Johns Hopkins.

When the university offered him the opportunity to go to what was the centre of tropical medicine back then, he seized it.

“Little did I know about Kolkata,” he chuckled before adding: “I was lucky to have a wife who believed in and supported me and who had a spirit of adventure. So, with her blessing, I accepted the position.”

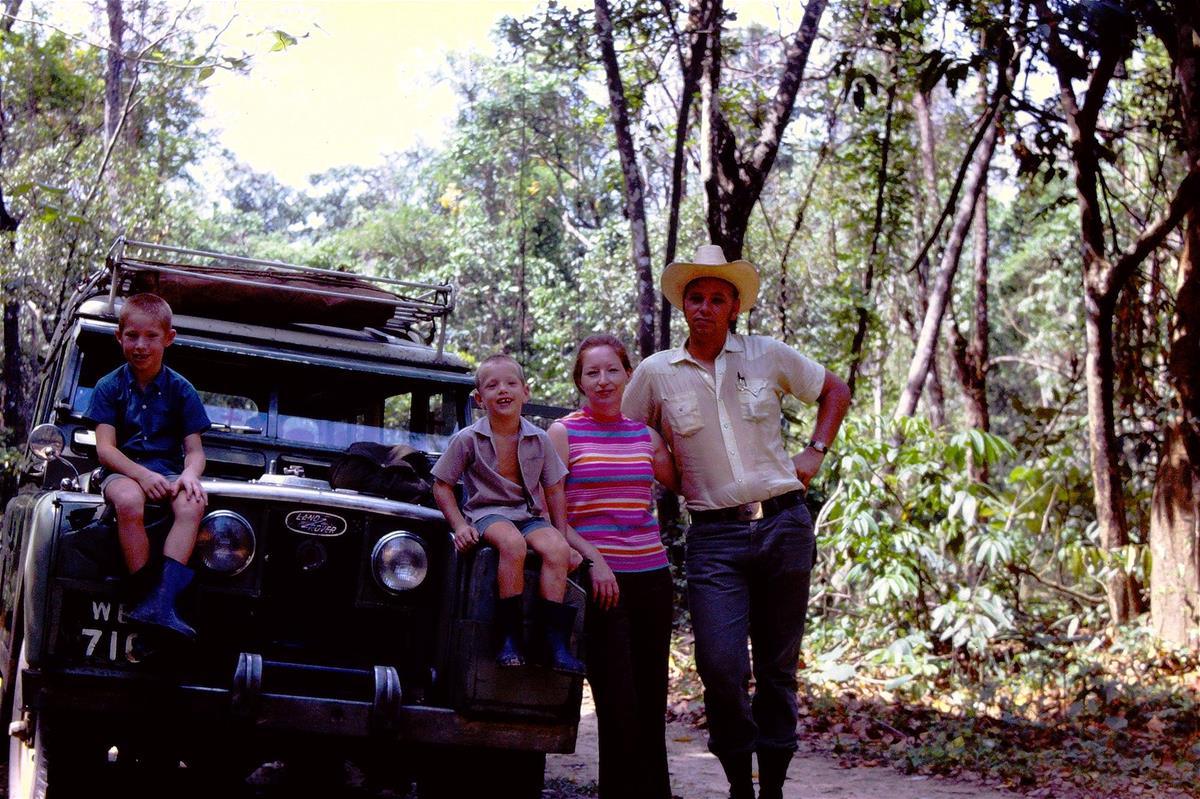

Duane Gubler, his wife Bobbie and two sons on a trip to the Sukna rainforest in 1970 // Credit: Duane Gubler

Right place, right time, right idea

There, Gubler focused on studying the real-world interaction between humans, mosquitoes and the parasite that is the leading cause of permanent disability worldwide: Wuchereria bancrofti, a round worm nematode that can cause extreme swelling of body parts, pain and severe disability.

Duane Gubler's team stands in the middle of the 100sqm study area in Kolkata, where they discovered that people were exposed to low levels of the Wuchereria bancrofti parasite almost constantly, thereby preventing them from developing severe disease // Credit: Duane Gubler

“I didn’t have a big budget, so I had a very small study area,” recalled Gubler.

But his 100 sqm study area was packed with people, animals, mosquitoes and anything else that went with early 1970s Kolkata. He found that people were exposed almost constantly through mosquito bites to low levels of the parasite—not enough to cause disease but just enough to stimulate an immune response, creating a balance now known as immune tolerance.

At the time, the findings were controversial.

“I had a hard time getting it published because the editor of the journal was an expert on this parasite himself and didn’t think that my argument was valid,” said Gubler.

It finally appeared in November 1974 in The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene and served as the case study on how to conduct field epidemiological research for public health students at Harvard for years.

A leap of faith

Gubler’s Kolkata time ended when political tension between India and the US escalated. His funding—along with that of other scientists—was cut off, leaving him at a crossroads.

Hopkins, a well-established institution, had offered him a promotion back in Baltimore. Yet around the same time, Scott Halstead, a renowned dengue expert, offered him a riskier opportunity: to join his nascent department of tropical medicine and medical microbiology at a newly founded medical school which would be co-located between the Leahi Hospital and the National Institutes of Health’s Pacific Research Section laboratory in Hawaii.

“I really had my doubts,” confessed Gubler.

But the opportunity to be a faculty member at the university while conducting exciting science alongside renowned scientists and mentors—including Leon Rosen and Halstead, two grandees in dengue research—swayed him.

“It was one of the best decisions my wife and I made,” said Gubler, who would return to the island state again in 2004 as the director of the Asia-Pacific Institute of Tropical Medicine and Infectious Diseases. “Leaving Hopkins to go to the University of Hawaii started a whole new trajectory of my career.”

That was the trajectory that would lead to him standing on the tarmac in 1974 with a dewar of mosquitoes that were once again spreading dengue. Effective mosquito control had almost eliminated the virus in the years following the war.

Duane Gubler looks down the microscope in his lab in Hawaii as he inoculates a mosquito // Credit: Duane Gubler

But before heading into the field, Gubler first had to develop a better way to isolate the virus from clinical samples, so that this epidemic could be studied.

“Mosquito inoculation was—and is still today—the most sensitive method of isolating these viruses,” said Gubler of the method he helped develop. He became so proficient at it, that he could inoculate more than 200 mosquitoes per hour.

“Even later in his life when he was no longer working the lab, he could still inoculate or dissect a mosquito as though it was routine work, or like riding a bicycle,” recalled Dr Milly Choy, who as Gubler’s PhD student at Duke-NUS had to master the skills of rearing and inoculating mosquitoes for her research. “This has not only taught me to be patient but also given me a first-hand understanding of mosquito biology that is critical for proper experimental design.”

With this technique set up in the lab in Hawaii, Gubler began tracking a newly resurgent dengue epidemic across islands, meticulously testing and recording what he found. Amid the epidemic, Tonga stood out. Despite being at the heart of the outbreak geographically, the kingdom had not reported any cases. Undeterred, Gubler headed to the island in search of dengue patients. He ended up going to the hospital every morning to scrutinise the overnight admission list in the hope of identifying potential cases and then tracking them down to collect samples.

Back in Hawaii, after inoculating mosquitoes with the virus, he realised that the dengue epidemic he had been tracking had reached Tonga, it just didn’t cause the severe disease that had plagued the other islands.

“The idea that even just a few genetic changes may be at play came from this work,” said Ooi Eng Eong, a fellow professor with Duke-NUS’ Emerging Infectious Diseases whose work focuses on understanding which mutations enhance the virus’ fitness and which ones weaken in.

This silent outbreak in Tonga cemented Gubler’s determination to set up an active viral surveillance programme to prevent the re-emergence of a virus that had been virtually eliminated in the Americas. And he got the opportunity to do just that when he was asked to set up the Dengue Branch in Puerto Rico for the US Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which would be dedicated to surveillance, prevention and control of dengue fever and dengue haemorrhagic fever.

“We are still learning from the data that came out from Puerto Rico,” said Ooi, who in 2015 published a paper in Science together with Gubler that documented for the first time how a few genetic changes can drive a dramatic change in the virus’ fitness, turning an endemic into an epidemic without a change in serotype.

Have a question? Send it in and it may be answered in the next issue of MEDICUS!

ASK MEDICUS

The meticulous records and extensive collection of virus samples collected over a career are part of Gubler’s legacy, according to the next generation of dengue researchers.

“Even now we have not characterised all the strains that he has collected,” said Choy, who is now a principal research scientist and the head of Duke-NUS insectary that Gubler had set up.

But more than the collection, it was Gubler’s open approach to its stewardship that had the most lasting impact.

“He was always very free in sharing what he had—whether it was insights that weren’t published or samples that he had collected. He enabled young scientists to grow, which was very refreshing. Many people, who are now very well established, really started with Duane’s support,” said Ooi.

Preparing for the next outbreak

As international air travel became more common, and people migrated to densely populated cities, Gubler’s concerns about the threat of infectious diseases increased.

“I was convinced that Asia would be the origin of newly emerging pathogens,” said Gubler, who foresaw a worldwide rise of dengue driven by globalization, urbanisation and a lack of effective vector control—a constellation he calls “the unholy trinity” of the 21st century.

“He wanted dengue on people’s radar because he realised, long before others did, that malaria would decline with modernisation,” said Wilder-Smith, “but it would be the opposite with dengue. And he really did that. He brought dengue out of its neglect.”

While Gubler travelled far and wide—including to Singapore—to support dengue surveillance, prevention and control programmes, gaining the same support he had in Puerto Rico was not always easy. In 2007, Gubler, who was by then back at the University of Hawaii, had all the pieces in place for a surveillance programme, led out of Hawaii, that could ring an early warning for the US mainland. In the end, the sustained investment required to form such a sentinel programme was too big a commitment for the university

“I walked out of that meeting and picked up the telephone to call Duke University in Durham,” recalled Gubler, who had been courted by Duke for a while by that point. “I said if that job in Singapore is still available, I’m available.”

Gubler became the founding director of the Emerging Infectious Diseases Progamme on 1 November 2007. Working together with Duke-NUS Senior Vice-Dean for Research Professor Patrick Casey, Gubler and Casey talked about war time: what was needed to prepare the world against emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases, in particular new zoonoses. Gubler also wanted the programme to serve as sentinel and reference laboratory for the region.

Duane Gubler with inaugural faculty members, two of whom—Professors Ooi Eng Eong (second left) and Subash Vasudhevan (second right)—remain core faculty members to this day // Credit: Duane Gubler

“Duane wanted to build a centre for excellence that didn’t just pursue academic research but was very much involved in shaping public health, and he did that with the programme at Duke-NUS for Singapore at least,” said Ooi. “Because what he advocates for dengue—active surveillance and prevention through vaccines and vector control—applies to many other viral diseases and should be part of any pandemic preparedness.”

In the end, the world needed the COVID pandemic to accept the true value of preparedness.

“Improving the network of regional surveillance and lab capacity to detect emerging diseases like the Centre for Outbreak Preparedness aims to do is close to what Duane has always envisioned,” mused Choy.

“Both Wang Linfa and Gavin Smith have taken the programme to new heights. It has become one of the best, if not the best, infectious diseases programme in Asia under their leadership.”

Prof Duane Gubler on what the programme has become

Casey, who had hired Gubler, added, “We owe an enormous debt of gratitude to Duane for his selfless efforts to spearhead the development of the EID programme at Duke-NUS and shape it into a leading programme not only in terms of research impact, but also in the training of the next generation of infectious disease professionals. This had great impact on Singapore’s readiness to face the COVID-19 threat.”

Out of all his accomplishments, for which he received the prestigious Richard M Taylor Award in November 2022, Gubler draws most satisfaction from the sustainability of the Duke-NUS programme and the Dengue Branch at the CDC: “I think the success of these programmes overshadows any of my scientific contributions.”

Duane Gubler, accompanied by his wife Bobby (left) and Duke-NUS Dean Thomas Coffman (third row, second right), marks his investiture as an honorary Singapore citizen on the steps of the Istana. He received the honour—the highest bestowed on foreign nationals—in recognition of his contribution to the country in the area of dengue surveillance, control, management and research in June 2022. // Credit: Ministry of Health, Singapore