May 2021

By Claudia Batz, Policy and Projects Coordinator, World Obesity Federation

‘COVID-19 has underscored, preyed on people living with obesity who are likely to hospitalised and have a higher likelihood of severe disease and death.’ – Dr. Tedros, Director General WHO

The past year has shown that health – and its neglect – is often a consequence of the society we live in and is determined by factors far beyond individual control. This holds true for people living with obesity (PLWO) who face a set of unmodifiable risk factors like family history and genetics, race, ethnicity and sex, as well as a set of modifiable risk factors like lifestyle habits and environments. To support a whole systems approach to address obesity, World Obesity Federation developed the ROOTS framework, which sets out an integrated, equitable, comprehensive and person-centred response. In the context of COVID-19, PLWO face significant increased risks - with 113% at increased risk for hospitalisation, 74% more likely to be admitted to intensive care and 48% higher risk of death [1]. The ROOTS framework was further refined at the Global Obesity Forum 2020 and set out immediate actions related to COVID-19.

Obesity is a chronic, relapsing disease that does not receive prioritisation commensurate with its prevalence and impact and is now rising fastest in emerging economies. But why should this discourse shift, particularly when considering COVID-19 vaccination programmes? A comparative approach between the Philippines (PH) and the United Kingdom (UK) will be used to better understand how we can enhance COVID-19 vaccination uptake without leaving PLWO behind. Both countries have important lessons to teach one another that when combined will contribute to future pandemic preparedness and successful vaccination programmes.

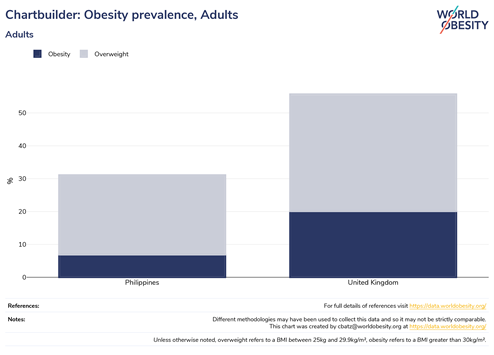

The PH is the first country in Southeast Asia to receive assistance under the COVAX programme, with 480,000 doses arriving on 4th March 2021, World Obesity Day [2]. As of May 2021, the country has the second-highest confirmed coronavirus cases in Southeast Asia, with a worryingly high number of reported deaths (8.67 deaths per 100,000 population) [3]. Meanwhile, the UK, the first country in the world to approve the emergency use of COVID-19 vaccines, experienced 14 times more deaths (110.73 deaths per 100,000 population) at the same point in time [3]. This is partly attributable to the difference in the prevalence of overweight and obesity (see figure 1). In the UK, over 50% of the population lives with excess weight. In the PH, the prevalence of overweight and obesity is approximately 30%. This is one of the highest in the ASEAN region. The trends in COVID-19 deaths support the World Obesity COVID-19 & Obesity Atlas predictions that countries with a prevalence of overweight and obesity >50% will experience 10 times higher mortality from COVID-19.

Figure 1 - obesity prevalence in the United Kingdom vs the Philippines (data from the World Obesity Federation's Global Obesity Observatory)

Figure 1 - obesity prevalence in the United Kingdom vs the Philippines (data from the World Obesity Federation's Global Obesity Observatory)

There are some stark differences between how the UK and PH handle their COVID-19 vaccination programmes and how PLWO in the two countries fit into the programmes. Below are some factors that must be addressed for a better understanding on the present situation considering lessons from the past for a more inclusive and effective future response.

Prioritisation: The UK offers COVID-19 vaccines to any individual aged 40 or over, with over 36 million individuals receiving at least the first dose as of 14th May [4]. In addition, people of any age living with severe obesity (a body mass index (BMI) of 40 or above) are considered at high risk from coronavirus and are eligible to receive the vaccine upon inquiry. In the PH, the vaccination rollout takes a tiered approach with frontline workers, senior citizens, persons with comorbidities and indigent populations in Priority Category A, teachers, social workers, and other essential workers in Priority Group B and the rest of the Filipino population in Category C. Unlike the UK, there are no specific eligibility criteria listed in the PH Department of Health Guidelines for PLWO [5].

Supply Constraints: The aim to vaccinate 70% of Filipinos in 2021 is going to prove challenging. People outside its priority groups are only expected to receive their first dose by August or September [6]. The PH relies on donor assistance to procure their supply of COVID-19 vaccines, from sources including the World Bank (WB) and the COVAX scheme. In March 2021, the WB approved USD 500 million to support vaccination for priority groups in the country [7]. While this boosts the overall vaccination rate, it does not address the urgent need to vaccinate PLWO who, as mentioned earlier, are not on the priority list. Furthermore, studies suggest that PLWO produce only about half the number of antibodies in response to a second dose of the jab compared with healthy people and thus may require a third dose [8]. Given the scarcity of vaccines in the PH, it is unlikely that third doses will be offered any time soon, leaving PLWO further at risk. The UK experienced its share of logistical challenges – particularly with Pfizer-BioNTech and its rigid storage protocol and Brexit trade deals portending disruption to supply chains. However, a shift in policy since January 2021 to delay the second dose has resulted in nearly 36 million people being vaccinated with the first dose as of early May 2021, making UK one of the countries with the highest vaccination rates globally [9].

Hesitancy and uptake: In 2017, the dengue vaccine controversy in the PH gave rise to distrust in both the vaccine, health care professionals and the government who controls decisions around priority orders for vulnerable groups. It was revealed that the Dengvaxia vaccine could cause more severe disease for people not having been infected, thus linking the mass vaccination programme to a ‘genocide against Filipino children’ [10]. The dengue vaccine controversy in the PH offers valuable lessons that are applicable internationally (see figure 2). It has highlighted the need to involve scientists in defining the schedule of priority groups by adopting an equity lens along with better transparency. The UK has implemented these lessons by taking caution after claims emerged suggesting that their very own Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine increased the risk of blood clotting amongst recipients [11]. Media campaigns urge ethnic minority communities and youth to get vaccinated. People-centred approaches have been used to address inequity in distribution.

Figure 2 - Lessons from the Dengue vaccine controversy in the Philippines

Figure 2 - Lessons from the Dengue vaccine controversy in the Philippines

Systemic issues: COVID-19 has the potential to exacerbate negative behaviours and attitudes that are directed to individuals because of their BMI. It is unclear if the high mortality seen for PLWO is a result of seeking care too late due to the fear of being blamed and shamed in clinical settings. Successful vaccination programmes that are inclusive of PLWO will play a key role in a return to a ‘new normal’ for this group. Such programmes should support obesity prevention, management and treatment efforts, while improving mental health by reducing feelings of distress and anxiety, a root cause of obesity. They also need to address common barriers to patient care during the pandemic such as connectivity, lack of equipment, trust, adaptation and expectations [12]. Coupled with reduced opportunities to be physically active, changes in eating behaviours and increased levels of food insecurity, governments should proactively address these systemic factors driving obesity. The UK has made a clear commitment to expand weight management services, equip staff to support PLWO and made it easier for everyone to make healthier choices and prevent obesity through its obesity strategy.

Conclusion:

While the UK is in a remarkably better position than January 2021, other countries, including the PH, are still struggling against the pandemic. New variants are emerging due to uncontrolled transmission, also causing fear that it may render vaccines ineffective. Rising infections and lockdowns pose threats that goes beyond the virus. People who require medical care and support, including PLWO, may not receive it on time. Even if they do, there are concerns that PLWO have diminished protection from COVID-19 vaccination based on influenza immunisation studies [13]. There is still no information available on the impact of obesity as a single factor on vaccination adequacy.

We must remember that COVID-19 is only the latest of a series of respiratory viral diseases that have affected human populations. There is every reason to assume that future infectious diseases will follow similar patterns and that an unhealthy population - i.e. an overweight population - will be at increased risk from future infectious disease outbreaks [4]. The impact on PLWO with every pandemic will only be exacerbated and thus they must be included and prioritised now before health outcomes deteriorate further. In the meantime, if we truly want COVID-19 to be over, we need to vaccinate everyone and ensure no one is left behind.

About the author

Claudia Batz

Claudia is an emerging public health professional and a youth advocate with three years of experience in global and public health. She is Policy and Projects Coordinator at the World Obesity Federation and a Core Team Member of Young Leaders for Health. At World Obesity, she supports the dissemination, communication, and utilisation of outputs from two EU consortium childhood obesity projects (CO-CREATE and STOP) and the development of youth-friendly materials, briefings and resources to help policymakers and others seeking to implement obesity-related policies in their countries. Her previous role involved supporting the enhancement and delivery of the Strategic Centre for Obesity Professional Education (SCOPE). Claudia’s work contributes to increased health literacy and brings the perspectives and skills of young people into the strategic design and delivery of health-related programmes and policies.

For any enquiries, please contact:

sdghi@duke-nus.edu.sg

The views expressed by authors contributing to the essay series are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of SDGHI.